Ted Black and Frank Durand explain why Johann Rupert should have listened to his mum TRENDY theories that treat people as “human capital” or “intellectual property” and “brands” as assets, argue for new business metrics to measure and value talent. They are red herrings. What is important is to harness people’s brains with the numbers we already have.

There are only two critical factors in business. One is to make money. The other is to generate cash.

Most managers and staff don’t understand that their financial rewards and long-term security depend on doing those two things. Moreover, they don’t know how to do it. Imagine what could happen if they did. Without the big picture that the financial numbers give, they just have a job.

Bruce Henderson, the late founder of Boston Consulting Group, cut to the heart of the matter: “A business is a cash compounding machine or it is nothing, and sooner or later will be swept away.”

“Get back to basics” always becomes the management mantra when companies hit bad times. The recent Remgro offer of R16 a share to minorities of RainbowChickens presents us a timely reminder of them.

The bid puts Rainbow’s value-of-the-firm (VOF) measure today at R4,6bn (share price multiplied by issued shares). It hit a year-end low of R230m in 1998. Anyone who bought shares near the time, probably most of today’s minorities, has done very well indeed. But what about Remgro itself? What kind of investment has it been? Furthermore, what lessons can we take from the Rainbow saga? It’s a great story.

The first is that no manager can act intelligently, or with integrity, unless he thinks like an owner all the time. It is a state of mind. No-one tells owners what to do. They work it out for themselves.

Despite all other demands, management has one legitimate purpose. It is to maximise the VOF for its owners — the shareholders.

Fundamentally, the VOF derives from the productivity of the asset base, not the workforce. Managers make a return on assets. Owners make a return on investment.

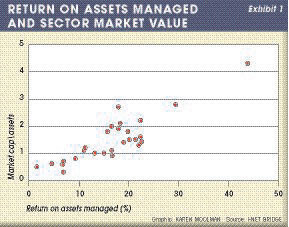

That is why return on assets managed (ROAM) is still the best measure for operating management and a great lens to use to seek and pinpoint productivity opportunities for people to tackle together.

You cannot be a first-class manager unless you understand finance. The ROAM model helps build that understanding. It requires no more than Grade 6 arithmetic and can be used to teach everyone the “great game of business”.

Ignorance about the rules of the game is widespread — even at the highest levels. The first responsibility of any manager is to educate his or her people in business basics to give them the big picture — never mind specific job skills.

The only valid measures of management intent and results are “resource in: result out” ratios. The ROAM model provides many of them. If used in the right way — to develop people — it triggers innovation, collaboration, teamwork and learning. Improved, sustained productivity follows.

Exhibit 1, above, shows Rainbow’s ROAM performance over 25 years. It sends the message: “All roads lead to ROAM … or ruin!”

Sadly, that message did not re a c h the owner, Johann Rupert, until it was too late. People at the top are too often the last to know when things go badly wrong. The dour people he charged to watch over his investment typified those who Adam Smith described in The Wealth of Nations in 1771: “The directors, being the managers of other people’s money, cannot be expected to watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which owners frequently watch over their own. Like the stewards of a rich man, they are apt to consider attention to detail as beneath them. Negligence and profusion, therefore, must always prevail, more or less in the management of the affairs of such a company.”

A 15-year decline resulted in a loss of R150m in 1996 and near bankruptcy for Rainbow. Following a rights issue to rescue the company, a furious Rupert stuck in another R600m, pulled on his gumboots and trudged around his chicken farm to find out what was going on. Did he own a sh*t chicken business or was he in a chickensh*t” business? It looked like both.

Facing the truth seldom comforts us. It is why crises can be so valuable. They force us to confront reality and take action.

The first truth Remgro had to face was that it had made some huge blunders. Strategic planning’s great contribution, if done well, is to trigger managed change — change that exploits proven strengths and maximises opportunities.

However, neither Remgro, nor a reluctant HL&H, which ended up running Rainbow, knew anything about chicken farming. Seduced into a honey trap, they matched opportunity with weakness — the first blunder — and the numbers followed the weakness.

Soon after listing, the company acquired Bonny Bird/Epol from Premier Milling — a monumental bungle. This one doubled up the asset base and created a very different company from the one built by its founder — the late, legendary Stanley Methven.

The move was based on the false premise that high market share results in high ROAM — that it is a cause-effect relationship. It is not. It is a probability, but a most unlikely one when you add nonperforming assets to low-performing assets.

Methven knew this. Despite many approaches from Premier — a milling company that got into chickens by default — he did not want his company to be contaminated by it. The story goes that he even celebrated the end of a short, disastrous foray into feed milling. With his team gathered round him in Hammarsdale, he raised a glass of French Champagne, and said: “If I ever get the urge to buy a feed mill again, shoot me.”

That’s another important lesson. Celebrate the mistakes, savour them, and learn from them.

Over the years, Epol had performed little better than break-even and Bonny Bird made a profit once in its history. Market analysts thought it a great move both for Premier and Rainbow, whose share price doubled. The VOF went to R1,7bn in 1992.

The capital market’s vote of confidence confirmed the 6th Higher Law of Business: “You can sometimes fool the fans, but you never fool the players.”

The first loss followed and the VOF dropped to R848m. However, a small profit a year later in 1994 duped the fans again. They pushed the VOF back to R1,3bn, showing that managers in charge of a sick company can produce a big rise in the share price with second-rate financial performance.

The players — Rainbow’s people — were not fooled. From 1996 to 1999, the company lost nearly R600m, confirming the 9th Higher Law: “If nobody pays attention, people stop caring.”

It was a disaster, and all to get one good brand, Farmer Brown, the only Premier “asset” really worth having.

The move also destroyed HL&H — a once proud, 150-year-old company. The social and economic costs were grave, confirming the 10th Higher Law: “Sh*t rolls downhill.”

With acquisitions, the golden rule is: “Don’t buy a standalone company, especially if you don’t know the business.” You will pay far too much unless you can uncover and release hidden productivity opportunities. It is better to buy a parcel of companies, sell the ones you do not want and get the one you do for a knockdown price.

Corporate managers nearly always pay over the odds. In contrast, successful entrepreneurs bid “low”. Knowing how to allocate capital well, they buy at a discount; sometimes for nothing if the target company is in distress. Seldom do they pay a big premium.

Macsteel, owned by Eric Samson, is a good example. Reputed to be the biggest privately owned steel trading company in the world, it has acquired many companies but Samson has never paid more than net asset value — usually less, or in the end, sometimes nothing.

There are good reasons why corporations pay too much. First, top management uses other people’s money. Second, professional advisers’ commissions and fees are linked to the size of the deal — the bigger the better. Third, executive pay is based on size of company and responsibility, not economic productivity. This brings us to the next measure. It’s a cash one.

Rainbow has been profitable every year since 1999, achieving its highest ROAM since 1982 — 21%. But has the turnaround been good enough to justify owning it?

As Peter Drucker put it: “Until a business returns a profit that is greater than its cost of capital, it operates at a loss. Never mind that it pays taxes as if it had a genuine profit. The enterprise still returns less to the economy than it devours in resources. Until then it does not create wealth; it destroys it.”

Economic profit is a true measure of management competence and it is a tough one. You can manipulate the share price for quite a long time before capital markets catch on, which is why corporate management prefers it to economic profit.

Funding comes from owners, lenders and suppliers. The cash buys assets that operating managers have to manage. None of it comes free.

Rainbow’s interest charge has always been low except in the mid- 1990s when debt reached R500m. Supplier credit is interest free, but not cost free. Inventory takes up space, needs management and generates many hidden costs.

Owners’ cash is also not free. Until you charge for it, you do not know if the firm has made an economic profit or not. It must not be so high as to miss the creation of it, nor must it be too low or the company becomes a cash trap.

If you look at other, better alternatives for investment that Rupert had to give up, it seems reasonable and defensible for him to have “charged” Rainbow management 25% for his money and the risk he took. If he had, then Exhibit 2, below, is an indicator of how much wealth his management destroyed from 1989. It is not a pretty sight.

The calculation is based on Stern Stewart’s EVA™ measure (net operating profit after tax less the actual cost of capital). It took until 2003 to create an economic profit equal to or better than a 25% return on equity. From 1989 to 2003, Rainbow returned R195m to owners for average equity of about R750m. That’s a 26% return in total for a 15-year investment, or only R13m a year—an annual return of less than 2%.

As a self-deprecating Rupert humorously admitted at a shareholder AGM in 1998, his late mother had told him not to buy it. She was right. It was, and probably still is, a disastrous investment if you look at the 20-year opportunity cost.

However, it is rare indeed for a business leader to have the courage and integrity to do what he did. Facing harsh reality and taking full responsibility leads to “breakthrough” and another important lesson.

The corollary to the 9th Higher Law that the stuff rolls downhill is: “Change must start at the top.”

Rupert intervened, picked his own man to run the show, and the turnaround started.

Most organisations have huge potential for improvement but unlike Rainbow, few achieve major breakthroughs. The successful ones have leaders who grasp what has to be achieved — the goal is clear. They also confront their people with the clear belief that it will be done and that they can do it.

Finally, they know that simplicity drives productivity. If you want change you do it with one number.

Most managers “manage by the numbers” but with too many of them. Daily, a torrent of data swamps us. Most of it means little. Moreover, the numbers are random — random within the system.

Before looking at the random numbers, let’s look at the system.

Rainbow’s latest annual report gives a clear picture of the value stream of activities. If it attached asset values to each activity it would be even more interesting and revealing (see Exhibit 3 below). The business model determines if you make money. The key to economic productivity is concentration and focus. It raises two strategic questions: “What assets should we own?” and “How do we control the rest?”

The most toxic of all business designs is unfocused, vertical integration. That is when a company owns everything. Rainbow was highly integrated in 1996 and still is.

To make money, you must be the lowest-cost producer or you must have something no one else has. Unless you have a unique product or service that makes you different, you have to compete on price.

The first strategic decision taken was to have good genetic stock. It affects the cost and quality of the bird on the plate. Your birds must grow faster, resist disease and end up plumper after eating less. Rainbow management had neglected this issue but corrected it successfully.

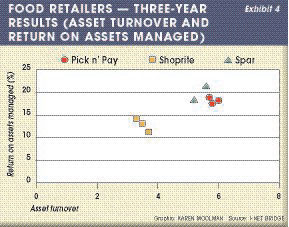

The ROAM model poses two marketing questions to test a business model. They lead to input:output ratios. The first is: “For every rand of assets we have, how many rands of sales do we generate?” (Sales divided by total assets is the measure and is called asset turnover).

Asset turnover is the most important measure of operating management and the least used. For Rainbow, it determines the capital cost of every kilogram of chicken sold — the first competitive productivity barrier for any firm.

The slower your asset turn, the lower your ROAM is likely to be. Exhibit 4, below, shows how management improved asset turnover steadily through to 2002.

The first task was to undo much of the Bonny Bird/EPOL acquisition. Plants were closed and farms sold. As asset turnover accelerated from 1,3 in 1996 to 2,4 in 2002, it cranked up ROAM from -10,9% in 1998 to 12,5% in 2002.

The first task was to undo much of the Bonny Bird/EPOL acquisition. Plants were closed and farms sold. As asset turnover accelerated from 1,3 in 1996 to 2,4 in 2002, it cranked up ROAM from -10,9% in 1998 to 12,5% in 2002.

Then as management started to reinvest in new plant from 2003, slowing asset turn down, the next ROAM marketing measure becomes more significant: “For every rand in sales, how many cents profit do we make?” This is return on sales (operating profit ÷ sales × 100). It improved steadily from 5,2% in 2002 to its highest level in 18 years— 14,1% last year. However, there are warning signs that today’s management is losing sight of the importance of asset turnover.

Watch out for marketing guys. They generate excitement and growth but have an Achilles heel. Asset productivity is not their strong suit. Because their mission is to please customers, give them the smallest gap and they expand and extend product lines, fill up warehouses with stock, discount it and then shy away from collecting money. This lowers the next ROAM productivity barrier: current asset turnover. It drives the measure that governs every company’s viability — the cash-to-cash cycle.

You must aim to have a lower level of stock and debtors per rand of sales than your competition. In Methven’s day, stock and debtors spun an average of 6,3 times a year — that is about a 58-day cycle.

Under HL&H it fell to an average of 3,9 — about 94 days — but reached a low of 3,5 (104 days) in 1997. Alarmingly, it is back there.

Exhibits 5 and 6, at right, use physical numbers to show what happened. The first shows sales in kilograms over a three-year period just before the crash started in 1996.

Exhibits 5 and 6, at right, use physical numbers to show what happened. The first shows sales in kilograms over a three-year period just before the crash started in 1996.

The pattern is typical for many companies. Although it shows random sales performance month on month, market demand was stable and predictable. It probably still is.

Reporting to the board, all the various Rainbow MDs could have truthfully said was: “Some months are better than others.” It would have not gone down well but would have been helpful.

Rainbow management could expect sales of about 3,5 tons of chicken a week for the foreseeable future. However, that is not how the organisation responded. Company plans often do not reflect market reality. Big, hairy, audacious goals set by gung-ho managers out to please their bosses can cause huge instability and distortion of information as it filters through people in the value stream.

Exhibit 6 shows what happened to inventory. It was “out of control”. At the end of this time series with stock leaping up, the company went on to record massive losses.

Not matching intent with reality is a common phenomenon. The dotcom bubble burst for a similar reason only a few years later.

“New economy” companies such as Solectron held $4,7bn inventory because of blue-sky forecasts from the likes of Cisco, Ericsson and Lucent. Cisco eventually “wrote off” $2,5bn inventory, axed 6 000 people and its VOF fell by $400bn.

With Rainbow, the velocity of current asset turnover increased from 3,5 in 1997 to 5,8 in 2002 and has slowed since then. At the 2006 yearend it was at 3,8 and wound down further to its 1997 level of 3,5 at end- September 2006.

To put the importance of competitive asset turn in perspective, compare Rainbow’s performance with Astral, the best-performing feed and poultry firm ( Exhibit 7 below).

Astral consistently outperforms Rainbow with an overall asset turn 30% faster on average over seven years; at year-end 2006 it was 60% faster. Astral’s current assets turn has averaged 6,1 for the past two years while Rainbow has slipped to average 4,1 — 50% slower and losing speed.

Astral consistently outperforms Rainbow with an overall asset turn 30% faster on average over seven years; at year-end 2006 it was 60% faster. Astral’s current assets turn has averaged 6,1 for the past two years while Rainbow has slipped to average 4,1 — 50% slower and losing speed.

However, with the next productivity barrier, Rainbow’s cost of sales dropped from 75% to 63% in 2006 — a great achievement, probably due mainly to the low maize price and shrewd buying. Today, it could be the least-cost producer off the farm.

Then there’s the fourth productivity barrier: “How do you differentiate a dead chicken and charge more?” Rainbow’s “innovative solutions” do not seem to be working yet. Cost seems to have more influence on profit than the so-called “highmargin” products that analysts and financial pundits waffle about.

For every rand spent on administration, selling and distribution, Astral generated R8,98 of sales, and output is rising. Last year, every rand of expenses for Rainbow generated R4,62 in sales, but fell from R6,50 the previous year.

In summary, Rainbow lags Astral with these key productivity measures except cost-of-sales. However, this is a message of opportunity. It is no accident that Rainbow’s improved ROAM has generated an economic profit and improved the VOF.

Asset turnover and sales profitability drive ROAM. They are two of the four levers that create economic profit. The others are growth of a productive asset base, and gearing. When management achieves a ROAM result that beats the cost-ofcapital, you can expect the VOF to keep rising.

The “new”, much improved Rainbow has more, huge untapped potential waiting to be released, confirming another higher law from The Great Game of Business: “The more successful you are, the bigger the challenges you have to deal with.”

It is the same with every firm. However, because of fear, we do not educate people with the numbers. We fear they may fall into competitors’ hands. So what if they do?

We fear that employees will misunderstand and use them against management. They probably will if we do not educate them.

Give them the big picture and you appeal to a higher level of thinking. You knock down the barriers of ignorance that keep people apart. When you do that, it leads to higher levels of performance and results on your road to ROAM.

Ted Black (black@icon.co.za ) is an executive coach focusing on converting problems and opportunities into action projects. Frank Durand is a senior lecturer at the Wits Business School in the fields of finance and asset management.

EXHIBIT 1 provides a context. The universal “S-curve” reflects an organisation ’s pattern of growth, effort and results over time. Two more underpin it. The first is the bumpy learning curve.

EXHIBIT 1 provides a context. The universal “S-curve” reflects an organisation ’s pattern of growth, effort and results over time. Two more underpin it. The first is the bumpy learning curve. EXHIBIT 2 trends some key ones. They are asset growth, the ROAM (return on assets managed) percentage and market capitalisation over the company’s lifetime since listing on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange in 1986.

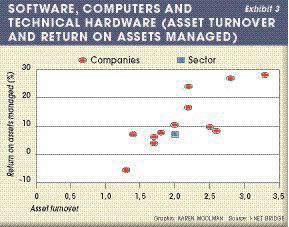

EXHIBIT 2 trends some key ones. They are asset growth, the ROAM (return on assets managed) percentage and market capitalisation over the company’s lifetime since listing on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange in 1986. EXHIBIT 3 shows the close correlation between its profit margin and ROAM since first listing on the JSE.

EXHIBIT 3 shows the close correlation between its profit margin and ROAM since first listing on the JSE. EXHIBIT 4 uses a statistical process behaviour chart — a valuable but rarely used management tool. It shows that the business model — the system designed by management — generates the numbers.

EXHIBIT 4 uses a statistical process behaviour chart — a valuable but rarely used management tool. It shows that the business model — the system designed by management — generates the numbers.

The first task was to undo much of the Bonny Bird/EPOL acquisition. Plants were closed and farms sold. As asset turnover accelerated from 1,3 in 1996 to 2,4 in 2002, it cranked up ROAM from -10,9% in 1998 to 12,5% in 2002.

The first task was to undo much of the Bonny Bird/EPOL acquisition. Plants were closed and farms sold. As asset turnover accelerated from 1,3 in 1996 to 2,4 in 2002, it cranked up ROAM from -10,9% in 1998 to 12,5% in 2002.

Exhibits 5 and 6, at right, use physical numbers to show what happened. The first shows sales in kilograms over a three-year period just before the crash started in 1996.

Exhibits 5 and 6, at right, use physical numbers to show what happened. The first shows sales in kilograms over a three-year period just before the crash started in 1996.  Astral consistently outperforms Rainbow with an overall asset turn 30% faster on average over seven years; at year-end 2006 it was 60% faster. Astral’s current assets turn has averaged 6,1 for the past two years while Rainbow has slipped to average 4,1 — 50% slower and losing speed.

Astral consistently outperforms Rainbow with an overall asset turn 30% faster on average over seven years; at year-end 2006 it was 60% faster. Astral’s current assets turn has averaged 6,1 for the past two years while Rainbow has slipped to average 4,1 — 50% slower and losing speed.  The best hope for SA would be a privileged, multiracial elite perched atop a simmering cauldron of repressed expectations never to be met. That’s a message of fear. Instead, take the next steps and go for the message of hope: reframe the problem into an opportunity and convert it into a simple, measurable goal.

The best hope for SA would be a privileged, multiracial elite perched atop a simmering cauldron of repressed expectations never to be met. That’s a message of fear. Instead, take the next steps and go for the message of hope: reframe the problem into an opportunity and convert it into a simple, measurable goal. Second, the basic rules of business have not changed one iota since the days of the pharaohs. So, you may ask: “What are these basic rules of business?”

Second, the basic rules of business have not changed one iota since the days of the pharaohs. So, you may ask: “What are these basic rules of business?”