The world cup is a breakthrough project able to harness dormant talent – Ted Black.

LIKE any new chief executive, SA’s “interim president” has to make today ’s business viable, unlock its hidden potential and turn it into tomorrow’s business.

LIKE any new chief executive, SA’s “interim president” has to make today ’s business viable, unlock its hidden potential and turn it into tomorrow’s business.

When you launch a business, you drive for a breakthrough with a superior product, technology or service that has big potential.

Kgalema Motlanthe has that in the Soccer World Cup 2010. It is a mission that can focus brains, win hearts and become a huge step forward towards our vision of a rainbow nation. The global soccer showpiece meets all criteria for a “breakthrough” project that puts participants on a learning curve.

Rainbow nation’ is the vision —2010 the mission

WE HAVE had some disturbing news recently for the good sailing ship SA (Pty) Ltd, and now there’s a new captain — albeit in an acting capacity. However, if President Kgalema Motlanthe acts like most leaders in his situation, he will make the job his own. If he really wants to do more than keep the seat warm for someone else, he will get results fast and have the most important power of all —performance.

WE HAVE had some disturbing news recently for the good sailing ship SA (Pty) Ltd, and now there’s a new captain — albeit in an acting capacity. However, if President Kgalema Motlanthe acts like most leaders in his situation, he will make the job his own. If he really wants to do more than keep the seat warm for someone else, he will get results fast and have the most important power of all —performance.

To get it, Motlanthe has to tackle the threefold management task common to all CEs. That is to:

- Make today’s business viable;

- Unlock its hidden potential; and

- Turn it into tomorrow’s business.

To continue with the sailing analogy, navigator Trevor Manuel has taken us into calmer economic waters after the stormy seas of apartheid years. However, there are storm clouds lowering on the horizon and we have Tito Mboweni at the wheel. He is steering a high interest rate course that has us sailing very close to the wind. He is “pinching” the boat and we have lost speed.

There is no doubt our ship is seaworthy but, like all of them, it needs constant maintenance, and we have failed at that. We also have our weaknesses and threats—the most serious of them come from within. The organisation’s climate, culture and values among officers and crew are lousy.

There has been a highly acrimonious tussle in the officers’ mess. To add to the unrest, the crew down below squabbles and fights in the destructive ways of the past. It is also mutinous and wants to plunder what it can. Others are jumping ship.

Sadly, that’s because we have followed a course over the past 10 years that has taken us a long way from former president Nelson Mandela ’s simple, inspiring vision of what Archbishop Desmond Tutu ’s words “rainbow nation” meant to him. He said: “Each of us is as intimately attached to the soil of this beautiful country as are the famous jacaranda trees of Pretoria and the mimosa trees of the bushveld — a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.”

Some leaders pooh-pooh the idea of visions and missions. That is because political bureaucrats write them for annual reports and outsiders. They become mere slogans. However, if articulated well, they point the way and inspire people to make a difference.

Mandela ’s words expressed the vision for us in a way that meets the criteria described by Jerry Porras and Jim Collins in a seminal article at Stanford Business School in 1989.

It should be concise and simple — simple enough to pass the “grandmother ” test. If she “gets it” then you have something that will hook your people. It has to meet a fundamental need and be convincing enough to last a hundred years. Its purpose is to arouse, excite and mean a lot to people inside the organisation. Lastly, you describe it in the present tense. You can already see and feel what the future will be like.

However, you need steps to get you there. They derive from the mission. In contrast to the ongoing purpose of a vision, the mission is a clear, compelling, urgent, exciting, time-bound and measurable goal. It moves you forward in a steady, unrelenting and purposeful way. It is demanding, even unreasonable, but you are going to tackle it anyway.

President John Kennedy’s vision for the US nearly 50 years ago was for the US to become the greatest, most respected nation in the world. The mission to land a man on the moon and bring him back safely within 10 years was a big step towards that.

Sadly for Americans, that vision, like ours under Mandela, is taking some big knocks today. So, coming back to SA (Pty) Ltd, what is the mission that can focus the brains, win the hearts and become a huge step forward towards our vision of a rainbow nation? It has to be World Cup 2010. It meets all criteria for a “breakthrough” project that puts you on a learning curve. When you launch a business, you drive for breakthrough with a superior product, technology, or service that has big potential.

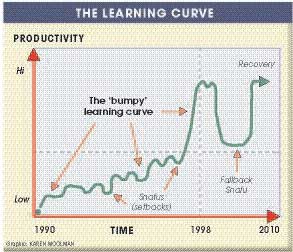

The curve in the exhibit below shows that a firm will not be economically productive during the start-up phase because of Murphy ’s Law: “If anything can go wrong, it will.” Those are the “Snafus” (situation normal — another f ***-up).

SA has reached the biggest Snafu of all — the fallback stage. We have been chasing numbers — not the vision of a rainbow nation.

Learning is hard work. It consumes energy, resources and time and always takes longer than you think it will.

However, viewed in the right way, the inevitable setbacks become stepping stones to success.

Once you reach a level of competence, the business is viable and can pay its bills. You have the platform to step onto the experience curve. Now you can make many, purposeful moves that tap into the hidden potential.

You standardise ways of doing things but keep improving them. You build teams; train people; develop, redesign and entrench new systems and procedures that take wasteful practices out of the system.

When people do the work together and share knowledge instead of competing with each other, productivity climbs and costs per unit plummet. You make lots of money and generate cash. Your company becomes a cashcompounding machine.

However, what the curve tells us is that you cannot simply switch people from competing with each other to co-operating and collaborating productively. It takes time and focused effort, although you can speed it up. That is where the “breakthrough” project comes in.

It demands change. This is unlike capital projects or annual performance goals, which do not change the way people do the work together. A breakthrough project does. However, you have to make an ego-free admission first and it is what our fallback is telling us: “The way we do things now does not work.”

There is a critically important presupposition behind this admission. It is the belief that no one reaches full potential. If you are very capable, and lucky, you will be above average but you get so far then stall.

Left to find your own way, you level off way below what you could achieve. A lack of awareness, challenge, criticism and testing stunts personal growth. This is true without exception. It applies to all organisations and leaders — for CEOs and their boards and for the president and his cabinet of ministers. No leader can afford to surround himself with “yes” men or to kill criticism from the public and media. It results in disaster as we see happening on our northeastern border —another threat to SA (Pty) Ltd.

Left to find your own way, you level off way below what you could achieve. A lack of awareness, challenge, criticism and testing stunts personal growth. This is true without exception. It applies to all organisations and leaders — for CEOs and their boards and for the president and his cabinet of ministers. No leader can afford to surround himself with “yes” men or to kill criticism from the public and media. It results in disaster as we see happening on our northeastern border —another threat to SA (Pty) Ltd.

Executive growth is evolutionary. It takes time and does not happen in a classroom. No successful executive ever attributes his or her success to a course or qualification. It is always some particular experience. However, you can accelerate it in a welldesigned situation.

To design it, use the conditions that drive people to tackle crises successfully. The factors that typify an emergency do not exist in the daily life of most organisations. Typically, people are frenetically busy doing exhausting work that adds little or no value.

A lot of the time, they are simply playing politics and pursuing their own agendas. They tackle false crises, not genuine ones. When you share stories about the genuine ones — fires, floods, strikes, and other “must-do” situations —they reveal two profound truths.

The first is that people quickly rise to the challenge. They do it without conferences, planning workshops, orders from above, consulting advice, motivational training or team building. Moreover, they do it with no additional resources.

The second truth is that it means every organisation owns and pays for significant, but unused, hidden capacity. A crisis uncovers this hidden potential because there is extreme urgency to get things done.

The goal is near and clear. People take charge. The challenge excites and stimulates them. They collaborate, ignore red tape and experiment. Politics and backbiting disappear. Depending on the nature of the emergency, they have fun doing what must be done. The results that these “zest factors” stimulate can be amazing.

The good news is that you can tap into this huge reserve of potential without burning down a factory or suffering a strike or blackout. So the challenge is for managers to release it. It is the same for SA and its new skipper.

World Cup 2010 has all the elements to unite the nation and to harness the hidden reserve of ability that lies dormant in our population. It is an exciting, breakthrough project — like Kennedy ’s 10-year moon mission.

Done well, it can have an effect on three factors critical to the nation’s success:

- Make the poor productive;

- Build a new generation of effective, ethical managers; and

- Develop tourism.

The mission must be to organise a Word Cup that equals or betters the “best” of all that have gone before and that provides an unforgettably positive response for all visitors to the country.

The 2010 World Cup provides a narrow focus. With communication, less is more. You change an organisation, and a nation, with one, simple, easily measurable goal —not many of them.

To get results fast, there must be a powerful sponsor and a champion with the clout to back team leaders as they cut through the Gordian knots of red tape.

You must have people in the teams who can contribute — not people who are “nice to have”.

This is no time for bureaucratic numbers — the only numbers that count are ones that measure results. There has to be regular review. We have less than 600 calendar days left to execute our own “moon mission”.

There is no doubt our ship is seaworthy but it needs constant maintenance, and we have failed at that

Chunk the 600 days into 100 day milestones. There are only six left. Within the 100 days, have 10- day milestones. That is 60 to go. Every six days that go by take us 1% closer to crunch time. This builds up a sense of urgency as you look at the accomplishment ratio — time lost against results achieved.

Chunk the 600 days into 100 day milestones. There are only six left. Within the 100 days, have 10- day milestones. That is 60 to go. Every six days that go by take us 1% closer to crunch time. This builds up a sense of urgency as you look at the accomplishment ratio — time lost against results achieved.

World Cup 2010 demands radical change in the way we manage our country. Maximising this opportunity will reposition SA and even Africa itself.

More important, it will kickstart the development of our managerial capacity.

Imagine the improvement in our self-esteem, self-confidence, competence and relationships as we celebrate the end of a hugely successful event. Moreover, our economic productivity will improve. The change in the numbers will reflect the growth in management ability and the way our people work together.

This project is far too important to be throttled by the dead hands of bureaucrats or politicians squabbling with each other. It calls for highly visible, active top-level sponsorship and involvement of “line management”.

Nothing should deflect us — not even next year’s election. There ought to be a “war room” or “bridge ” in the Union Buildings. In it, the new skipper should be able to review at any time a portfolio of projects that have an effect on the overall mission.

If World Cup 2010 is to be the next major port of call for the good ship SA (Pty) Ltd, let us be sure firstly that the crew does not “run ashore” to rape and pillage.

Secondly, let us ensure that more than 90% of the visitors who climb up the gangplank to explore the ship leave us with a resounding “Yes! ” to this one question: “Will you tell your relatives and friends to visit SA at the first opportunity they have?”

Ted Black (jeblack@icon.co.za) helps managers to design results driven projects that grow them and their people measurably.

EXHIBIT 1 provides a context. The universal “S-curve” reflects an organisation ’s pattern of growth, effort and results over time. Two more underpin it. The first is the bumpy learning curve.

EXHIBIT 1 provides a context. The universal “S-curve” reflects an organisation ’s pattern of growth, effort and results over time. Two more underpin it. The first is the bumpy learning curve. EXHIBIT 2 trends some key ones. They are asset growth, the ROAM (return on assets managed) percentage and market capitalisation over the company’s lifetime since listing on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange in 1986.

EXHIBIT 2 trends some key ones. They are asset growth, the ROAM (return on assets managed) percentage and market capitalisation over the company’s lifetime since listing on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange in 1986. EXHIBIT 3 shows the close correlation between its profit margin and ROAM since first listing on the JSE.

EXHIBIT 3 shows the close correlation between its profit margin and ROAM since first listing on the JSE. EXHIBIT 4 uses a statistical process behaviour chart — a valuable but rarely used management tool. It shows that the business model — the system designed by management — generates the numbers.

EXHIBIT 4 uses a statistical process behaviour chart — a valuable but rarely used management tool. It shows that the business model — the system designed by management — generates the numbers.