“The future of the planet, and of SA, depends on effective management”

Focus on margins prevents managers from creating wealth, writes Ted Black

AFTER 1994, a rather arrogant, patronising, white, male old guard passed on to a new generation of inexperienced managers and owners some very sophisticated and complex organisations in both the private and public sectors.

Today, the new generation is discovering how difficult it is to run them. And the focus has not changed —it remains the same as the old guard: to maximise sales margins and redistribute wealth, not to create it. The prime lever for improving performance is not through improving productivity of resources but through the power to set and control prices. It is quick and relatively easy, but it is not sus tainable.

From a shareholder’s point of view, management still has only one legitimate purpose — to maximise the value of the firm. Mo r e – over, the value derives fundamentally from productivity. That is where the focus needs to be.

We cannot ignore the elephant sitting on our stoep

As we read of our steady slide down the world’s productivity rankings, then gaze north at Zimbabwe and elsewhere in Africa, we cannot ignore the elephant on our stoep. When are we going to stop taking money and start making money?

Peter Drucker described it in 1980 in Managing in Turbulent Times: “Only managers — not nature or laws of economics or governments — make resources productive.” I would add that you get sustainable productivity only when there is a sense of community — when all people feel they belong and are in it together.

Robert Mugabe has destroyed that in Zimbabwe. Where is SA heading? What are the omens?

Forget the hype about the need for leaders. The future of the planet, and of SA, depends on effective management.

Business literature swamps us with stories about leaders pointing the way and changing people with their visions. A lot of it is rubbish. throughout history, the reality is that few leaders have done that and four recent ones are Lenin, Stalin, Hitler and Mao.

Besides, how many of us want to be led anyway? We might like to be trained, coached, and developed by mentors we choose. We may even agree to be managed in the right way —but not led.

As to South Africa Inc, for this fledgling democracy to succeed we have two critical factors to address — make the poor productive and build a new generation of management. These issues should drive everything we do in the government and the private sector.

We need fiscal discipline, but the blunt instruments of free market monetary and interest-rate controls bludgeon the very people who have least influence over rising inflation—the poor. The negative effects on growth and job creation could damage us seriously and destroy the already fragile community and family structures in SA. The most fruitful way to tackle the thorny issues facing South Africa Inc is to lift productivity and create wealth that everyone can share.

During the previous century a small proportion of this country’s population prospered because of abundant mineral resources. Commodity exports were the lifeblood of the economy and still are. In effect, a mining camp spawned the industries we have today. Moreover, the government protected them with its political system, high tariff barriers and subsidies.

Judged by world standards, these hot-house conditions created highly profitable firms run by quite capable management.

In our Third World economy, with value based on limited beneficiation of exported commodities, corporate strategy was to gain preferential access to raw materials. This meant that productivity focused on low input costs and high pricing tactics in local markets. The aim was to maximise dividends, minimise equity holdings here and to shift money overseas.

Little has changed, except our management. After 1994, in the rush to meet affirmative action and black economic empowerment (BEE) quotas, a rather arrogant, patronising, white, male old guard passed on to a new generation of inexperienced managers and owners some very sophisticated and complex organisations in both private and public sectors.

Today, the new generation is discovering how difficult it is to run them. What is more, our focus is still to maximise sales margins and redistribute wealth — not to create it. The prime lever for improving performance, whether it be for municipalities, Eskom, or private firms, is not through improving productivity of resources but through the power to set and control prices. It is quick and relatively easy, but it is not sus tainable.

In the developing world a major barrier to improving productivity is financial illiteracy. Many of us have a phobia about numbers: we cannot do simple arithmetic and have only the vaguest notion of how business works.

Most people think that money cascades magically through an organisation into their bank accounts on the 25th of the month, whether they get the work done or not. Moreover, more employees are now shareholders with no clue as to what that it means for them.

To compound the problem we have a corporate governance movement that aims to influence boards and have companies compete and prosper in an ethical way —to make society a better place for everyone. However, it stresses social responsibility more than economic results and productivity.

“Business literature swamps us with stories about leaders pointing the way and changing people with their ‘visions’. A lot of it is rubbish”

Despite good intent, it’s hard to measure what it wants. A triple bottom line and balanced scorecards hold no-one to account.

From a shareholder’s point of view, management still has only one legitimate purpose — to maximise the value of the firm (VOF). Moreover, the value derives fundamentally from productivity.

By shareholders we do not include in-and-out traders looking for short-term gains. We mean investors who put their cash in a company expecting an economic return for a long time.

They see management as being ethical, competent and effective — people who do the right things in the right way because they think and act like owners. When that happens, shareholders become more than investors. They become long-term savers.

An example of a company that provides such opportunity is Berkshire Hathaway. As James O’Loughlin wrote in his revealing book, The Real Warren Buffett: “Buffett says he does not understand the CEO who wants lots of share activity: that can be achieved only if many of his owners are constantly exiting. At what other organisation —school, club, church — do leaders cheer when members leave? If this were the case, then Buffett would not be able to fulfil his function as corporate saver —the proper function of the stock market.”

In the 2007 annual report, Buffett says: “We do not view the company itself as the ultimate owner of our business assets but instead view the company as a conduit through which our shareholders own the assets.”

He says they are not “faceless members of an ever-shifting crowd but rather co-venturers who have entrusted their funds to us for what may well turn out to be the rest of their lives”.

Contrast that view of management with former General Electric CEO Jack Welch who said: “Being a CEO is nuts! A whole jumble of thoughts comes to mind: Over the top. Wild. Fun. Outrageous. Crazy. Passion. Perpetual motion. The give-and-take. Meetings into the night. Incredible friendships. Fine wine. Celebrations. Great golf courses. Big decisions in the real game. Crises and pressure. Lots of swings. The thrill of winning. The pain of losing.”

Nice work if you can get it! Clearly, he was no corporate saver but he did manipulate Wall Street very skilfully, and that helped pump up the share price no end.

Whether he allocated capital very well is a moot point judging by General Electric’s relative economic performance over the years. Sorry to say he has become a model most modern managers want to emulate.

In stark contrast, Buffett and his colleague, Charlie Munger, see themselves as managing partners and see shareholders as owner partners. It is why today about 30 000 of them rock up for Berkshire’s annual meeting. At the end of one year the same investors who owned them at the start of the year held 97% of shares. That makes them savers, and for good reason.

The result of Buffett’s stewardship is a compounded gain on investment of 21,1% a year from 1965 to 2007. That’s a 400 863% gain over 43 years. The S&P 500 over the same period achieved 6 840%. The VOF today is more than $200bn. Apart from investments in companies, the firm has 76 operating businesses. It is a diversified conglomerate employing 233 000 people. Only 19 of them work at HQ.

There is no share option scheme — Buffett doesn’t believe in them. They violate the principle of rewarding people for their own efforts in their own units. However, most of the key managers of the operations are independently wealthy and none has left the group to work elsewhere.

Buffett delegates to the “point of abdication” as he puts it, and says that HQ has a twofold task. First, it is to “create a climate that encourages (key managers) to choose working with Berkshire over golfing or fishing. This leaves us needing to treat them fairly and in the manner that we would wish to be treated if our positions were reversed.” He rewards them handsomely for making an economic return on capital in their own companies and for sending all surplus cash back to HQ. That’s where he fulfils the second part of the “owner’s” task — to allocate capital for acquisitions or investment.

As he puts it, “our carefully crafted acquisition strategy is to wait for the phone to ring”. The bigger the company the greater his interest will be. He responds to an approach within five minutes if it grabs his attention. He never does an unfriendly takeover and his attitude to start-ups, auctions or turnarounds is, “When the phone don’t ring you’ll know it’s me.”

He looks for well-run businesses “with a fortress-like business franchise ” — a product or service that is needed and wanted, with no perceived close substitute and which is not subject to price regulation. Owners usually run the firms he buys and he keeps them doing it after he buys control. It is how he gets good management into Berkshire Hathaway.

He wants high levels of profitability from a low capital base and low operating costs. In other words, he seeks low risk, high return, cash fountains — not cash drains. Businesses like that don’t need reinvestment to sustain them. Another criterion he looks for is that they must be simple enough for an idiot to run because sooner, or later, one will. In other words, he sets out to minimise risk and maximise return through a simple agenda.

The chart in the illustration, In the shareholders’ shoes, shows how he might position an opportunity. Behind the four quadrants are 17 business safety ratings cases —they provide clear, unambiguous signals for shareholders to rate managerial per formance.

Most managers picture an entrepreneur as a hardened risktaker who shoots from the hip. This viewleads to the master myth of management: all things being equal, higher returns reward higher risks. Driven by the myth, corporate cowboys, egged on by greedy merchant bankers, lawyers and accountants, head for box one.

They might as well be going to a racetrack or casino. They end up in box four where you find the wreckage of corporate start-ups, mergers and acquisitions, the result of high-risk, low-return strategies. Winning firms achieve lowrisk, high-return positions. Only companies positioned in quadrant two will satisfy the long-term shareholder as Buffett sees it.

So, what does his simple agenda mean for the corporate governance movement, company boards and even the South African government? Giving management and employees share options, as so many firms are doing, won’t make them think and behave like owners. You have to do more than that.

“In reality most organisations operate in ways that switch off the brain”

Just as a firm has an external marketing programme to win the minds of investors, it needs an internal one for results. It is the only way to surmount what Buffett calls the “institutional imperative”. We paraphrase his description of it:

- As if ruled by Newton’s First Law of Motion, institutions resist any change in direction;

- Just as work expands to fill available time (Parkinson’s law), managers chase the big projects and acquisitions that drain cash;

- Corporate troops (the bureaucrats) quickly support any business craving of their leader no matter how foolish it is; and

- Firms mindlessly imitate peer companies, whether they are expanding, acquiring, or setting executive pay.

Buffett says that when he went to business school he got no hint of the imperative’s existence. If he went back to one today he probably still wouldn’t. He thought decent, intelligent and experienced managers would make rational business decisions and he learned that they do not. When the institutional imperative takes hold, and it does in government too, rationality wilts.

It wilts because managers reduce the fear of uncertainty by asserting control. They do it with plans, budgets, forecasts and they manage systems and people by decree. However, this approach triggers other needs —the need for survival and the pursuit of selfinterest. Improving productivity, and allocating capital and resources efficiently and effectively are not the priorities that the business safety ratings can reveal.

In Buffett’s view, the strategic plan creates the institutional imperative. That’s why he doesn’t have one. He believes it gives him his greatest advantage. It means he lets go of the bureaucratic controls that a corporate HQ exerts, the exact opposite of the typical manager. His leadership style conforms to Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu ’s description: “Intelligent control appears as no control or freedom. For that reason, it is genuinely intelligent control. Unintelligent control appears as external domination and that is why it is really unintelligent.”

The institutional imperative becomes a heavy blanket that stifles people’s potential. We talk of the value of human capital and business academics want it put on the balance sheet. However, in reality most organisations operate in ways that switch off the brain.

As to his operating companies, Buffett wants a crocodile-filled moat around the fortress. He urges his managers: “Widen the moat: build enduring competitive advantage —delight your customers, and relentlessly fight costs.”

Growth is not the aim. However, his productivity goals generate the cash returns he then uses for growth opportunities.

In summary, he gets his key managers to focus on productivity — the most powerful competitive weapon for a business and a country. He has no strategic plan and gives no forecasts. The world is too random for that.

This approach frees him and his managers to pursue the vision of thinking and acting like owners. He can allocate capital where, when and at a pace that suits him — not Wall Street.

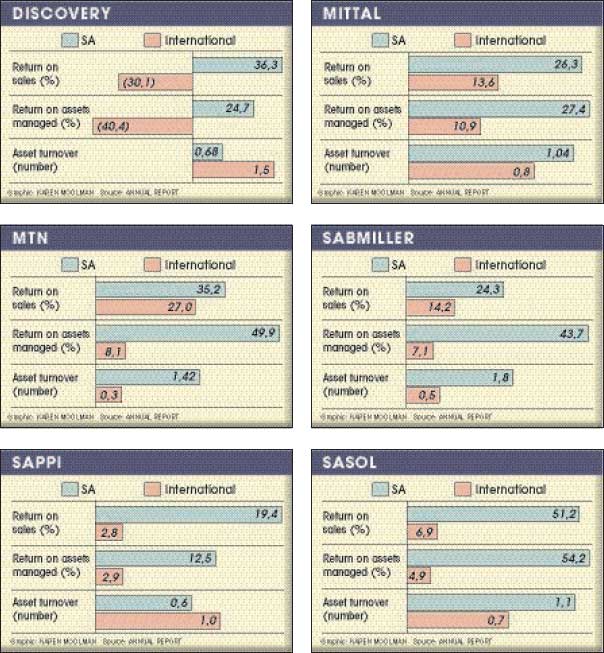

Given this perspective, we wonder how a board that focuses on productivity would view South Africa Inc and some of its diversified portfolio of industries and companies. Using the ROAM model (return on assets managed) and operating margin (operating profit/sales%) on a small sample of big players, we compare the profitability of their domestic operations with their global ones.

You can draw your own conclusions from the accompanying charts. Four conclusions stand out in my view:

- South Africa Inc is still seen as high risk and is not run by corporate savers;

- This means South African citizens pay through their noses for the internationalisation strategies that follow from that perception;

- South African management is not as good as it thinks it is when facing the heat of competition;

- This is because the productivity focus overseas shifts from pricing tactics to the sales productivity of the asset base — the other prime measure within the ROAM model. This is the sales/assets ratio known as asset turnover (ATO).

South African management is not good at managing productivity because there has been no pressure to do so. It involves work on the entire supply chain through to customers. The goal is to drive out the wasteful activity that exists throughout the value/cost chain— to lift everyone’s productivity — and to speed up the time from paying to being paid. The benefits come through to the customer in more competitive pricing.

However, there is another conclusion that defines the elephant on the stoep even more clearly. The sanctions era under the National Party government entrenched a policy of import parity pricing that led to inefficient resource allocation. Its effects persist today. Even ANC government policies protect high-cost industries that are uncompetitive by world standards.

The long-term weakening of the rand creates huge price overrecovery. This is when a producer charges an excessive price — as most South African institutions seem to do. They extract an everincreasing price subsidy from consumers. This guarantees profit growth but management becomes complacent. With no competition it just becomes a case of cost-plus pricing that encourages waste and low productivity, all to our economy ’s detriment.

A nice example of this in our sample, apart from the obvious ones of Sasol and Mittal, is Sappi. With Mondi, it forms an oligopoly — a small group of typically very large firms that collude to exert power and control over pricing — as we have seen exposed in the steel and food industries.

At first glance, this firm’s low returns — it has an overall ROAM of only 6% — do not reflect the benefits of a monopolistic position. However, you can see from the chart how Sappi takes advantage of the South African consumer with a 19,4% ROS. It is even higher because that figure includes exports at a much lower selling price than its local customers pay.

There is a deep-seated problem with the paper industry. Pe ter Drucker wrote in 1974 in Management Tasks and Responsibilities that since the Second World War the paper industry “has substituted capital for labour on a massive scale. But the trade off was a thoroughly uneconomic one. In fact, the paper industry represents a massive triumph of engineering over economics and common sense.”

“If we are serious about productivity and increasing our national competitiveness we have to change behaviour”

Thirty-three years later in San Francisco on October 22 2007, Eugene van As, at the end of a long career with Sappi, 30 years of it as CEO, candidly endorsed Drucker’s view. “For the past 20 years the top 100 paper companies have collectively destroyed value consistently every year.”

As a wag in the South African paper industry put it: “So why was he there so long? He should have left long ago!” His remark was more colourful than that but it’s the gist of what he said. Many shareholders would probably agree. They have a low-return, relatively high-risk investment.

When it comes to risk, there are two key elements — productivity and price recovery. We define productivity as units sold divided by resources units used.

Improving this rate lowers product cost (all the costs of getting products ready for sale) and lifts profit. It also lifts business safety, because it lowers risk. A low product-cost firm deters competitors. Moreover, it is never that easy to copy what others do.

With ready-for-sale costs, because of the institutional imperative, the potential for improvement is huge. The lean-thinking movement proves that we add cost with value for a tenth or less of the time between paying suppliers and getting paid by customers. That means for 90% of the time or more we pile up costs without adding a cent of value.

Corporations such as Tiger Brands write about “continuous improvement” programmes in their annual reports. What do they mean? Continuous improvement is not about improving what you do well. It is about eliminating all the things that stop you from doing what you do well — all the headaches. That’s waste. It’s what you have to look for and eliminate.

Management — or we should say bureaucrats—design waste or fat into the systems and procedures that people have to follow. It exists everywhere you look. We don’t see it because we don’t look for it. The only people who do see it and live with it are the people doing the work. Rarely do we ask for their ideas on how to remove it. Even more rarely does management act on them. It means that their brains never get out of bed in the morning. They just have a job.

The second major factor is price recovery measured as sales price/resource price. If you use a high selling price to make money without keeping product cost down, you increase risk. We call this price over-recovery. Typically it arises from sales price growing faster than resource price. This lowers business safety.

Managers use price over-recovery to subsidise a company’s ine fficiencies. However, high selling prices linked with low productivity send a signal that provokes competitors to attack. They steal customers with lower prices and better service.

The safest way to make money is to generate high productivity and use some of it to keep selling prices down, which is price underrecovery. You charge less but operate more profitably off a lower cost base than your competitors.

Productivity and price recovery determine business safety. They qualify the sales productivity of the asset base — the most important measure of all. It enables you to measure the productivity of capital —the real capital cost per unit sold — and creates a focus on speeding up the time from paying to being paid. This is sales revenue/ marketing assets managed. It drives ROAM, economic profit and ultimately the VOF.

If we are serious about productivity and increasing our national competitiveness we have to change behaviour. As effective managers know, the best way of doing that is through measurement and feedback, not visions and pep talks.

You only have to tell people you will be measuring them. Even if you don’t give them the measure, the very thought of it will change their behaviour in some way. So, it makes sense to have ones that they believe in and trust.

In the late 1970s, during a severe drought in Clarens in the Free State, no matter how much the town fathers urged everyone to save water nothing happened until the doughty town clerk intervened. She published the names of every householder, showing how much water each used a month. Only then did behaviour change and consumption drop. That’s the power of public measurement.

We could have monthly publication of what we term business safety ratings (BSR). They would apply to all private and publicsector entities. They give clear signals on productivity and price recovery. Boards can use them as part of internal management development and performance improvement programmes and investors can use them as part of their risk-return evaluations.

An additional possibility is that government could apply tax incentives to companies which engage in price under-recovery because they would be lifting productivity to do it and remain viable. It can be done. It just remains for us to start doing it and we will.

In future articles, I will analyse companies to derive business safety ratings and see how big the elephants sitting on the corporate stoeps really are.

Ted Black (jeblack@icon.co.za) coaches and conductsROAM workshops that help managers design results-driven projects.